The Neuroscience Behind a New Era of Test Taking: Paper vs Digital

The differences between paper and digital notes are often stark, especially when factoring in the academic performance associated with typing and handwriting.

Reading Time: 4 minutes

Imagine sitting at a desk, in front of a test paper, hoping that all the time you’ve spent printing out practice questions, highlighting important sections, and writing annotations in the margins will pay off. Now, imagine all of that time spent using paper and pencils is no longer useful when you have to take a digital test. If this surprising change happens, how impactful could digital test taking be for students who have only prepared for paper tests?

When studying for tests, regardless of if the format is digital or paper, students share a common goal to retain the information they’ve learned in order to be well-prepared. In 2021, a study of the University of Tokyo’s Japanese university and graduate students concluded that writing on physical paper leads to higher brain activity, allowing for more information retention after an hour. University of Tokyo neuroscientist Kuniyoshi L. Sakai, the research article’s corresponding author, found that paper is more useful than electronic documents for studying since paper contains unique information—such as the physical qualities and spatial arrangement of the characters on the page—that allows for stronger memory recall. The study’s volunteers had an objective to complete a note-taking task, and the volunteers who used paper completed the task 25 percent more efficiently than the volunteers who used digital notes and devices. Even though the volunteers who wrote digital notes used a stylus pen and a digital tablet (compared to a keyboard), the study’s researchers discuss that paper notes have more complex spatial information (such as the wrinkles in the paper, uneven lines drawn, inconsistent pen strokes, etc.) than digital notes. Paper’s complex spatial information likely contributed to the increase in note-taking and improved recall, since paper activated more regions of the brain through these unique pieces of information. From this research, Sakai concludes that, to learn and memorize information faster, paper notes are the way to go.

Beyond that study, key neuroscience concepts that support this conclusion. When comparing handwriting to typing, another study’s author has found that handwriting activates a broader network of brain regions involved in various types of processing, such as cognitive, sensory, and motor functions. These brain regions include the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus, which help in structuring the information as it is written, storing written material more effectively for recall and more. On the other hand, typing engages fewer neural circuits, resulting in more passive engagement (less actively involved) of brain regions. To conduct this research and reach these conclusions, the researchers first performed a comprehensive PubMed search using broad imaging-related keywords (e.g., MRI, EEG). Next, they narrowed their focus to studies involving human neuroimaging on typing and handwriting. Finally, the team reached conclusions (such as handwriting activating more neural circuits than typing) through group consensus, which were then documented in a PRISMA flowchart—a diagram showing how the researchers were able to narrow down all the studies found within their database search to a smaller number of studies used in their research study.

In Marano’s study, the main regions of the brain discussed were involved in cognitive, sensory, and motor processing. The regions of the brain involved in handwriting include, but are not limited to, the following: the parietal areas: superior parietal lobule (SPL), which facilitates spatial orientation, such as staying on the lines of the paper, and the inferior parietal lobule (IPL), which supports visual perception and motor execution, such as seeing a letter and reproducing it. The sensory areas somatosensory cortex (S1) processes the tactile feedback like holding the pen, movement, and pressure, whereas the cerebellum fine tunes coordination, the rhythm of writing, and more. On the other hand, typing is more automated and involves fewer fine motor skills (the ability to perform precise and coordinated actions) and less complexity. The regions of the brain that are involved in typing include the motor cortex (which controls the finger taps on the keys, but requires less “thinking” and complexity than shaping letters on paper), the cerebellum (the rhythm and coordination in typing/how fast someone is typing).

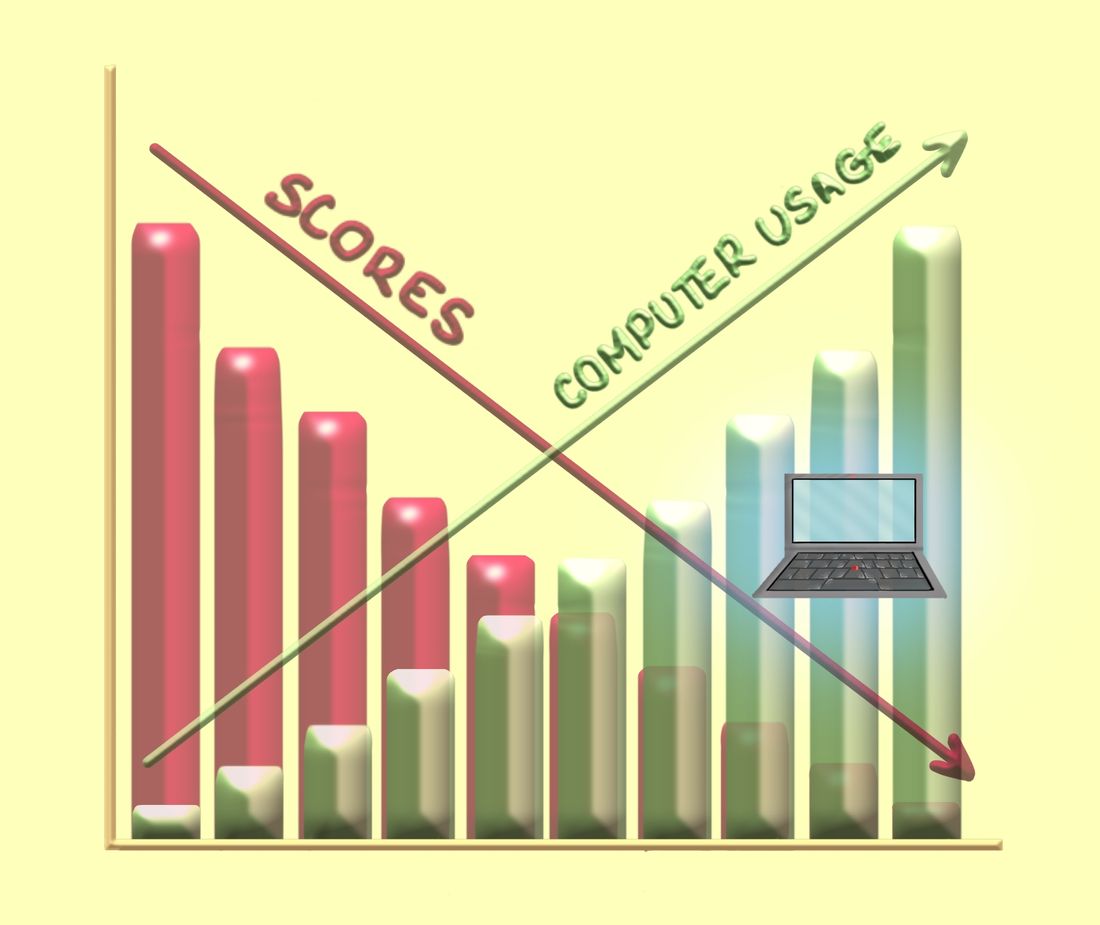

Despite previous studies describing a more efficient way to retain information using paper instead of digital notes, there may be many obstacles as standardized tests shift from paper to digital. Does the parallel of physical notes being better than digital notes align with paper tests being “better” than digital tests? Many tests, such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and the American College Testing (ACT), have switched from physical to digital formats. American Institute of Researchers scientists James Cowan and Ben Backes investigated whether or not digital tests correlated with lower test scores compared to physical tests. In their study, they saw a correlation describing how two students, similar in academic level, received different grades on the same test. The student given a physical test scored higher than the student given a digital test.

Aside from the evidence regarding testing scores and the brain regions activated when taking digital notes versus physical notes, a potential conclusion could be that digital tests lead to lower test scores. However, further research is needed, and until then, these tests will likely remain digital for the foreseeable future.